In celebration of Hispanic Heritage Month and with September being National Wilderness Month, we would like to kick off our spotlight series with George Wright – a pioneering Salvadorian conservationist who is to thank for the development of the National Park Service’s Wildlife Division in 1933. Although his career lasted for less than a decade, Wright made groundbreaking contributions to the conservation field that are still reflected in environmental policy today.

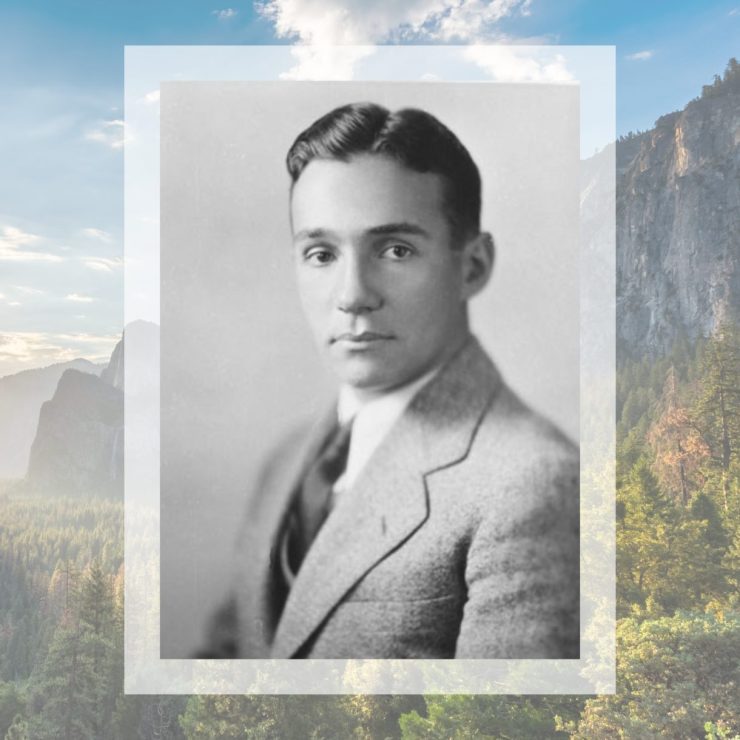

George Melendez Wright was born in June of 1904 to a successful family in San Francisco, California. Losing both his parents while still young, Wright was raised by his step-grandmother, who frequently encouraged him to go outside and explore the city. This inspired his love for nature at an early age and led him to major in Forestry at the University of California, Berkeley.

After graduating in 1927, Wright was hired as an assistant park naturalist at Yosemite National Park, making him the first Latino professionally employed by the National Park Service (NPS). While in this position, he taught field classes, wrote articles for Yosemite Nature Notes, and even contributed to the development of the Yosemite Museum. It was at this point that Wright also began to develop growing concerns about what he described as “problems caused by conflict between man and animal through joint occupancy of the park areas”. There was an abundance of deer, a scarcity of predators, and rampant uncontrolled human activity (i.e. hunting, feeding animals trash, littering, etc.). No scientific wildlife research or management was being conducted in any of the national parks, and he was determined to change this.

Wright developed a proposal for the National Park Service’s first wildlife biology plan and gained approval to direct an unprecedented survey of wildlife and their issues in the western national parks. Due to limited funding from the NPS, he ended up using over half of his father’s inheritance to fully fund the multi-year survey and pay the salaries of his two colleagues, demonstrating his unwavering dedication to the project.

With the help of partners Joseph Dixon and Ben Thompson, Wright ventured through the western parks and gathered their extensive research to publish Fauna of the National Parks of the United States: A Preliminary Survey of Faunal Relations in National Parks or Fauna No. 1 in 1932. Fauna No. 1 was the first in an array of NPS publications containing wildlife survey results, research, and recommendations for effective, science-informed wildlife management. For over 30 years, the text served as the definitive guide for wildlife management in the National Parks.

The Wildlife Division of the National Park Service was officially developed in 1933, and George Wright was named the first division chief. He moved to Washington DC and worked with elected officials to pass environmental policy, with a particular focus on wilderness preservation. Wright was appointed head of the Natural Resources Board by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1934, and under his leadership, parks across the country began regularly observing and surveying wildlife to identify potential threats. This continual monitoring led to the formation of restoration recommendations and allowed more attention to be paid to rare and endangered species.

In his last few years with the National Park Service, George Wright traveled the country to research areas where new national parks could be developed and worked with Mexico to establish protected areas along the border. He was tragically killed in a car accident at just 31 years old while on a mission from the newly instated Big Bend National Park in Texas. After his passing, the NPS Wildlife Division couldn’t keep the momentum going, and struggled to obtain adequate staffing or funding until the environmental movement of the 1960s.

Wright’s groundbreaking work for the NPS is still relevant today as we continue the fight for wildlife protection and wilderness preservation. His legacy remains in parks and wild areas across the nation, reminding us of the importance of science-based environmental policy to protect these spaces for generations to come. In honor of his visionary leadership, the George Wright Society was founded in 1980 and currently works to support parks and other protected areas in the US. Additionally, there are mountains named after him in both Denali National Park and Preserve (Alaska) and Big Bend National Park (Texas).